It appears that five months prior to Shreveport mayoral elections, the race card is being played in a decidedly ugly fashion by supporters of the only announced black Democrat in the contest.

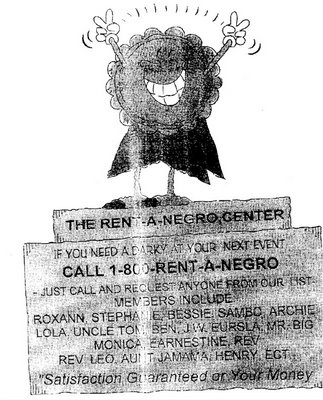

Here’s an example of a flier going around town, and at least one supporter of television executive Ed Bradley admits to passing them around. Baruti Ajanaku (you can see where he’s coming from in his comments to the Shreveport City Council in 2002 over redistricting) claims he found a stack of them at the Pete Harris Café and liked them, so he started passing them out. Ajanaku has benefited monetarily from the Bradley campaign, for what he says was buying copies of his musical CD.

The flier essentially berates by name black politicians and activists who dare to show anything other than opposition to announced white Republican candidates for mayor, because to do so it implies means you cannot genuinely be “black” or be for black interests. A paid advertisement in the Shreveport Sun that ran recently also largely mimics the flier’s attitude and naming of names. Without these individuals specifically committing themselves and thus recommending to their supporters they may influence to the cause of a black candidate, these media essentially try to pressure them into acting like mind-numbed robots not permitted to use their intellects and judgments to make their best choice for a mayoral endorsement, or even not to allow them to associate with members of the political spectrum with whom they may or may not agree and/or support.

Naturally, this argument is idiocy at the highest level. Conservative policies promoted by the GOP have done and promise to do more for blacks, other ethnic minorities – and to be most precise, just people in general – in all areas of policy such as economic advancement, education, and freedom to worship, among others. Democrats, often black politicians themselves, generally have left a trail of broken promises to the black community and care about the community only insofar as it gets them votes to stay in power, which they manipulate to do this by using on it scare tactics totally divorced from logic and the real world. (And, of course, it was white Democrats who kept blacks in political servitude in the South for many decades.)

But, more disturbing is the attitude the Bradley campaign has taken concerning the flier. To date, Bradley’s campaign has done everything possible to downplay anything having to do with race. From a review of his campaign website you could not tell whether he is a Democrat, and without any pictures whether he is black (although there are pictures of him with prominent white supporters, as well as testimonials from them). Yet Bradley himself has refused to condemn the fliers or the ads.

This represents the crudest kind of politics. No doubt Bradley knows Shreveport’s history where blacks largely vote for black candidates and (to a lesser degree) whites for white ones. Trends still show that on election day the plurality of the electorate in Shreveport will be black. Media castigating blacks who dare to not oppose whites in order to create a kind of racial solidarity that can translate into a winning majority may be tactically beneficial, but also puts the campaign into serious jeopardy of hypocrisy.

Bradley can’t have it both ways – presenting a nonracial image to his campaign in the hopes of attracting white voters, yet tacitly permitting racist media to encourage racial solidarity among black voters that also could mine votes for him. In no uncertain terms he must condemn these media, lest he become known as a race hustler for political convenience rather than as a serious, thoughtful supplicant to the mayor’s job.